Unlike here in Cascadia where octopuses live in the trees and are preyed upon by Sasquatch, on Okinawa, hominoids are arboreal and fear octopuses.

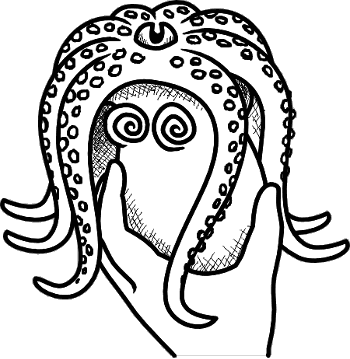

The above painting by Matthew Meyer -- part of his A-Yokai-A-Day series that you can buy as a print -- depicts Kijimuna in trees fearful of an octopus threatening to climb up after them.

Kijimuna (キジムナー) are a species of arboreal island hominoids native to Okinawa. Their diminutive size compared to Sasquatch, Yeti, etc. is probably a result of insular dwarfism and their partial baldness a likely adaptation to the subtropical climate. They live mostly in banyan trees, but will venture onto the ground to go fishing or interact with Humans. Human-Kijimuna relations have been strained in the past due to arson and flatulence. Human Okinawans often accuse Kijimuna of mischievousness, but this is probably Human chauvinism; we rarely get to hear the Kijimuna viewpoint in Okinawan media. (For more on Kijimuna, see Chicago Okinawa Kenjinkai's Kijimuna page or the Japanese Wikipedia.)

But what's the deal with the octopus? In his blog post about his painting, Meyer partially explains:

One final fact of note about kijimuna — they loathe octopuses! I am so far unable to discover why they hate them so much, but the lowly octopus is the one thing they cannot stand. Kijimuna will avoid them at all costs, so keeping octopuses around is a fairly foolproof way for humans to avoid potential kijimuna-related troubles.

I think Meyer has inadvertently shown in his painting the reason for octopusophobia among Kijimuna: a dispute over territory and resources.

As I have noted before (see: "The Ara-Eaters: Tree Octopuses Of Polynesia" and "Nicharongorong: Tree Octopuses of Micronesia"), octopuses in the South Pacific are drawn to trees, and many have adopted arboreal or semi-arboreal lifestyles. On Okinawa, this arboreal niche has already been occupied by the Kijimuna, denying octopuses there the "green embrace" they so desire.

Octopuses are persistent and determined creatures. They would simply not abide not being able to tentaculate through the banyans, nibbling on the figs. (Athenæus in his Deipnosophistae relates that besides olive trees Mediterranean octopuses [polypus] "have also been discovered clinging to such fig-trees as grow near the seashore, and eating the figs, as Clearchus tells us, in his treatise on those Animals which live in the Water." [Source.] Presumably Pacific octopuses would likewise be fond of banyan figs.) Octopuses are also greedy (a trait noted in Japanese culture -- see: Kure Kure Takora), so sharing the trees is not an option.

Kijimuna, hanging as they are in the way of the octopuses' sense of Arboreal Manifest Destiny, would surely attract octopodous belligerence. It's not unreasonable to assume that centuries, perhaps millennia, of stealthy attacks and attempted incursions into their trees would have instilled in the Kijimuna a healthy, and justified, paranoia about octopuses.